Latin for Gardeners

October’s Native Maryland Plant

Juncus effusus L.

(JUN-kus eff-YOO-sus)

Common Name: Soft Rush

October is Riparian Buffer month¹ – a time to reflect on the waterways that surround us and how we can each play a part in maintaining their health, for ourselves and for all the life that lives in, on and around our shorelines. The word riparian is from the Latin word ripa, meaning "bank" or "shore”, the Latin noun for river is riparius. Riparian refers to the land that borders a river or body of water – including forests, floodplains or the outskirts of wetlands. Buffers are things that form a barrier to protect against or moderate the impact of other incompatible things. Riparian buffers are vegetated areas that safeguard streams and aquatic ecosystems from harmful things like stormwater pollution (pesticide, fertilizer, …), animal waste and sediment while also creating habitat and providing cooling shade to rivers. Raising awareness of the benefits and need for riparian buffers is one way we can all help preserve the health of the waterways we enjoy.

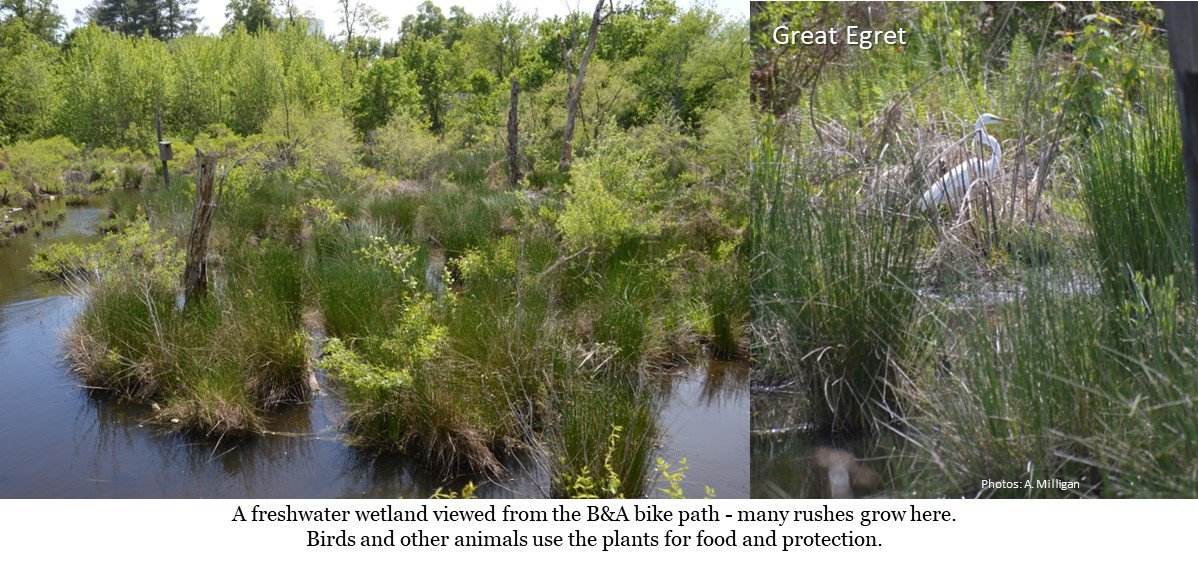

Juncus effusus is a plant often found in riparian buffers. Its fibrous roots help stabilize embankments and uptake nutrients - a major contributor to algal blooms. Its seeds are eaten by waterfowl while its long arching stems provide them protective habitat.

Many animals eat the seeds of Juncus effusus, including rabbits, songbirds, and waterfowl. Rushes provide habitat for amphibians and spawning areas for fish. Herons feed on the rootstalks of soft rush, and various wetland wading birds find shelter among the stems.

Juncus effusus can be an aggressive plant, its rhizomes weave together to provide excellent erosion control and to suppress weeds. Because of its ability to tolerate total inundation and drought stress, Juncus effusus is especially useful in rain gardens or landscapes with fluctuating hydrology, a common feature in Maryland residential properties.

Our riparian areas can’t wait to be buffered from the increasing harm of stormwater pollution. This fall we should all rush to find ways to use Soft Rush (or other native plants), in our own landscapes or communities, to help protect our streams and to provide habitat for the fauna that we love.

¹ https://www.chesapeakelandscape.org/riparian-buffer-month/

Alison Milligan – MG/MN 2013

Watershed Steward Class 7/CBLP